Zeno's Paradox of Plurality and Proof by Contradiction

This is an article I wrote back in 2002 when I was at UCI, in support of a fledgling journal at the time called “Mathematical Connections” that sadly didn’t last, and so far as I can tell is no longer available, except perhaps on the wayback machine. Here was the link, for those inclined to look: http://www.aug.edu/dvskel/Campbell2002.htm

I’ve always liked this little article, and so I’m posting it here, especially as I’ve had my head wrapped around that intriguing gap between the finite and the infinite over the past little while, trying (fruitlessly?) to prove the Collatz Conjecture.

For those who may wish to cite the original, here is the reference in APA format:

Campbell, S. R. (2002). Zeno's paradox of plurality and proof by contradiction. Mathematical Connections. Series II (1), 3-16.

It is all one to me where I begin, for I will return there again in time

—Parmenides

Zeno's paradoxes have been a source of inspiration and bewilderment for almost two and a half thousand years. Indeed, Aristotle considered Zeno of Elea (c. 450 B.C.E.) the father of dialectic, a form of reasoning that does not seem to be unrelated to the logical forms of reasoning underlying mathematical proof. Of all Zeno's paradoxes, the most renown, or at least the most familiar, are his paradoxes of motion. Much lesser known are Zeno's paradoxes of plurality. According to Proclus, Zeno composed as many as forty of these paradoxes, all but three of which have been lost. Here I will be concerned with what has come to be known as Zeno's second paradox of plurality:

If there are many, it is necessary that they be as many as they are, neither more nor fewer. But if they are as many as they are, they must be finitely many.

If there are many, the existents must be infinitely many. For there are always other existents between existents, and again others between these. And thus the existents are infinitely many. (adapted from Vlastos, p. 371)

Within a broader historical and philosophical context that takes into account Zeno's background and motivation for generating this peculiar kind of reasoning, I will attempt in this article to show a way in which it can be seen to encapsulate, in embryonic form, an approach to mathematical proof widely known today as proof by contradiction.

Proof by contradiction, or indirect proof, presents notorious difficulties from a pedagogical point of view, and many approaches to make it more accessible to students have been proposed and explored. These approaches have ranged from embedding it more deeply into real life contexts, to giving more attention to helping students translate it from natural into symbolic language, to teaching it as a special case of a more general logical schema, to allowing students with opportunities to study it in less formal and more reflective ways, to attempts to side-step its use to whatever extent possible.

As a complementary alternative to these approaches, I present a pedagogically viable reconstruction of the historical origins and philosophical motivations leading up to, and following from, Zeno's paradox of plurality. This is a fancy way of saying that I am going to tell a story about all of this. I will be less concerned with scholastic rigor and detail than I will be with engaging the reader with a rendering of how and why this may have all come about in the first place. It is my hope that this form of contextualization will shed some light on a well-known ancient proof by contradiction of the irrationality of the square root of two — the origins of which Otto Toplitz has indicated have been covered in "complete darkness".

Homeric Beginnings

There was a time when the Greeks were a preliterate society. Eventually, around the 8th Century B.C.E., the Ionian Greeks, living on the Western shores of Asia Minor and actively trading with the Phoenicians, gained access to papyrus from Egypt and acquired a semitic alphabet which they adapted to their own language. Prior to this time, however, the Greeks were heavily steeped within their oral traditions and the mythological modes of thinking they had developed over the many years within that tradition. Once writing took hold — and it spread quickly from Ionia throughout the Greek world, a watershed event commemorated to this day by the scroll overlaying the Ionic column — the Greek way of thinking about their world began to change quickly as well.

It is not a coincidence, then, that the first Greek physicists were from Miletus, the main city-state port of Ionia. Through their trade with the Phoenicians, the Ionians traveled widely, learning much about Babylonian and Egyptian cultures. Gradually, a radically new way of thinking about the world, exemplified by Milesian physicists such as Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes, began to emerge. This new way of thinking can be seen as a "depersonalization" or "naturalization" of the more traditional Greek mythological ways of thinking. Instead of thinking about the impetuous gods that controlled the seas and earth and sky, they became more interested in the tempestuous seas and earth and sky in and of themselves, referring to them as "the elements." Perhaps as a residue of their mythological mind set, they also began to wonder which elements were more important than the others. Thales claimed that all things had their origins in water, Anaximenes claimed that air was the primary element, while others would make similar claims about earth and fire.

The Origins of Science

There was something about Anaximenes' claim that was particularly important. Amongst other things, he provided a principle of compression and rarefaction whereby all of the other elements could be derived from air. As air was compressed it would condense into water, and if compressed further it would eventuate into earth. On the other hand, as air was rarefied, it would become fire. The significant thing about Anaximenes theory, or way of seeing, was that it introduced a bona fide scientific principle to explain the origins and transformations of the natural world of phenomena. Eventually these early Greek thinkers became conscious of the fact that these principles were not of that world. That is to say, these principles had a quality about them that was intrinsically different from the qualities of the natural objects perceptible to the senses. Perhaps it is this very realization that led Anaxagoras to proclaim that "Mind (nous) is the finest of all things and the purest; it has knowledge about everything and the greatest power; and it controls all things both the greater and the smaller that have life." Perhaps it is not entirely coincidental that "Anaxagoras' Nous is in direct line of descent from Homer's Dios Noos, the Mind of Zeus". Here, or so it would seem, the post-literate scientific assimilation of the traditional, preliterate, Greek mythological mind set reaches an apex: what Snell has referred to as the Greek "discovery of the mind."

All Things Accord in Number

It is possible that without the emergence of science in ancient Greece, there would be no such thing as Western Philosophy as we have come to know it. Nor, I would like to suggest, could mathematics have developed as we have come to know it either. The origins of Western philosophy and mathematics are not unrelated. In fact, they appear intimately bound together. Indeed, according to Iamblichus, Pythagoras (c. 550 B.C.E.) coined both terms. Pythagoras was yet another Ionian, born on the island of Samos, just off the coast of Asia Minor. From what little is known of him, and it is often difficult to separate fact from fiction, he was very well-traveled and knowledgeable in both Babylonian and Egyptian methods of reckoning. Whether or not he actually proved the geometrical theorem that bears his name, by whatever means may have constituted the meaning of "proof" in those times, there is something else he has been credited with that is far more profound, and far more germane to my story.

Not unrelated to the Greek Orphic tradition, through which creation itself was believed to be manifest in music and song, the great Pythagorean revelation was in realizing that number held the key to understanding the harmonics of the monochord, and more generally, according to Aristotle, the harmonia of the cosmos itself. The dominant harmonies of the monochord revealed themselves in the rations of 2:1 (the octave), 3:2 (the fifth), and 4:3 (the fourth). The sum of the unit, along with the numbers 2, 3, and 4, gave a total of 10, the tetractys, which was considered to be "the source and root of everlasting nature".

These peculiar beliefs of the Pythagoreans were not totally groundless. In identifying the unit with the point, 2 with the line, 3 with the plane, and 4 with the tetrahedron, they believed that they had discovered the fundamental elements from which all things were composed. Moreover, in taking number as the grounding principle of all things, the Pythagoreans began to identify the essence of different things, and the relations between them, with different numbers. Thus, they believed they could understand those essences through the properties and relations of those numbers. Insofar as the Pythagorean notion of the unit had spatial extension, and therefore a material nature, this view basically constitutes a proto-atomic theory. From a philosophical perspective, however, the more important implication to emerge from Pythagoreanism was that mathematics, in the forms and ratios of number, held the key to understanding the relationship between the newly discovered realm of mind and the naturalized phenomenal realm of the senses. It would come as quite a shock to realize that there were fundamental relationships, such as that between the side and diagonal of the square, that defied rationality.

Parmenides and the Way of Truth

If Iamblichus and others are to be believed, Parmenides (c. 480 B.C.E.) was a Pythagorean, one who would, I suggest, through his discovery of distinctively logical principles, precipitate events leading to the first foundations crisis in the history of mathematics. Parmenides, inspired by his teacher, Xenophanes, was literally carried away by the daughters of the sun, in his contemplation of the divine intellect, into the presence of a goddess who instructed him on the true nature of being. As Parmenides tells the tale of his revelation, in the fragments that have survived, he was instructed by the goddess in the ways of truth and seeming: The way of truth, an eternal realm in which things are and cannot not be; the way of seeming, a transient world in which things come into and fade out of being. As Parmenides envisioned it, in the way of truth, "...that what is is uncreated and imperishable, for it is entire, immovable and without end. It was not in the past, nor shall it be, since it is now, all at once, one, continuous.". According to Kirk and Raven, Parmenides has "... taught us all that reason, unaided by the senses, can deduce about Being. It is like a sphere, single, indivisible and homogeneous, timeless, changeless and, since motion is itself one form of change, motionless as well. It has in fact no perceptible qualities whatever" (ibid., p. 279).

Thus, for Parmenides, the way of truth is the one true being that can be grasped by intellect alone. The way of seeming, on the other hand, is the contradictory world of the senses, a world that can be created and a world that can perish, a world where opinion, not truth, occupies the minds of men. The way of truth becomes a path leading directly to the right and just realm of intellect, a realm governed by Parmenides' bivalent principle of non-contradiction: that which is is and that which is not is not. That is to say, that which is cannot both be and not be [One wonders if Shakespeare read Parmenides]. Ultimately, it is this principle, the principle of the excluded middle, that governs the logic underlying mathematical proof to this day.

Zeno and the One and the Many

Parmenides concluded that the way of truth implied that there could be only one, there could not be many, as his Pythagorean brethren appear to have believed. But, one must ask: one or many what? It is helpful at this point to consider for a moment how unlikely it would have been for Pythagoreanism to remain static in such a fervent intellectual milieu. Rather, it seems more likely, especially with the increasing awareness of the difference between sense and intellect, that the Pythagoreans would eventually refine their view in such a way as to liberate their foundational numerological units from the realm of the senses. Indeed, such a development may well have marked a break with the Pythagoreans with the emergence of Atomists such as Leucippus and Democritus (c. 440 B.C.E.). Either way, the debate over the one and the many can be interpreted in ways that remain deeply problematic to this day.

From a purely mathematical point of view, the debate may very well have revolved around whether or not the Pythagorean ratiocination regarding whole numbers was sufficient to cover the continuum. Indeed, scholars are beginning to analyze Zeno's second paradox of plurality with exactly such considerations in mind, particularly with regard to denumerable and nondenumerable infinities. However, we need not take such lengths in jumping ahead in my story, for we will arrive in short order at a similar, and much more familiar, place soon enough.

We have now arrived at a point where we can now consider what Zeno was up to with his paradoxes of plurality. According to Plato, Zeno confesses, in response to the dogged questioning of the latter's young Socrates, to have composed in his collection of paradoxes of plurality simply in defense of Parmenides, who had been coming under heavy ridicule for his position regarding the one. Plato records Zeno's position as follows: "... the book is in fact a sort of defense of Parmenides' argument against those who try to make fun of it by showing that his supposition, that there is a one, leads to many absurdities and contradictions. This book, then, is a retort against those who assert a plurality. It pays them back in the same coin with something to spare, and aims at showing that, on a thorough examination, their own supposition that there is a plurality leads to even more absurd consequences that the hypothesis of the one.

The Problem of Participation

As innocent and naive as Zeno's response seems, it is quickly evident there is more going on here than meets the eye. The young Socrates is critical of Zeno's overall approach regarding his paradoxes of plurality. He stands singularly unimpressed that all of Zeno's arguments against plurality simply come down to something like the following: "if things are many ... they must be both alike and unlike. But that is impossible; unlike things cannot be like, nor like things unlike" (ibid., p. 922). This is an observation to which Zeno readily agrees. However, when the young Socrates then rightly notes that such arguments are absurd when applied to everyday objects, for all such objects are like other objects in some ways, and unlike them in others, Zeno notes that Socrates has "not quite seen the real character of my book" and that "there is a point that [he] has missed at the outset" (ibid.). Indeed, as this dialogue unfolds, it becomes evident that Plato has an ulterior motive. He has staged this dialogue to explore how his own theory of intellectual forms holds up to Parmenides' and Zeno's arguments. Fortunately, understanding Plato's theory of forms need not concern us here. That is because Plato's theory is a philosophical theory that attempts to understand how the way of truth, and the realm of intellect, "participates" in the way of seeming, the realm of the senses. This is a very difficult issue that Plato was not able to bring to a satisfactory resolution.

The Way of Truth and Proof by Contradiction

I burden the reader with this brief but hopefully bracing excursion into deep philosophical waters for two reasons. First, because it helps to emphasize on no uncertain terms that Zeno is not in any way concerned with the way of seeming or how his arguments may or may not play out in the realm of the senses. As we can see from Socrates' objection in the previous paragraph, if he was, his arguments would be completely trivial. My second reason for this excursion is that Plato's concern regarding the relation between the realms of sense and intellect, which is also a fundamental problem for mathematics educators, will be both revealed and exemplified by something incredibly simply and deeply profound about whole numbers. But I will save this until the end.

We can now return to consider the second paradox of plurality presented at the beginning. Hopefully, it will be evident that the compelling power of this paradox comes from the fact that Zeno is applying Parmenidean logic in the way of truth — to a purely intellectual realm where things either do or do not exist. In the realm of the senses, according to Parmenidean logic, contradictions are allowed to exist, and indeed, usually do exist. Zeno assumes that Parmenides' detractors are following in the way of truth. In so doing, he then concludes, in what seems to be a reasonable manner, that there must be finitely many. But he also concludes, in what also seems to be a reasonable manner, that there must be infinitely many. Given that these two conclusions contradict each other, it must be that the assumption that there are many must follow the way of seeming, and cannot follow the way of truth. To see how this serves as a defense for Parmenides' assertion regarding the one, consider the following reasoning: By the law of the excluded middle, something either is or is not the case; In this case, either "one" or "many"; Not "many," therefore, "one."

The astute reader may have noticed the implicit use of truth preserving syllogisms that would not become fully explicated until Aristotle's treatment thereof in his Organon. Furthermore, there are some subtleties that have been overlooked here regarding the possibility of nothing existing that Parmenides does give some consideration to and discounts as impossible. However, what is most important about all of this is not so much the validity of Zeno's assumptions or the soundness of his arguments, so much as the dialectical or logical form of this manner of discourse. Bearing this in mind, we can proceed directly to show the connection between Zeno's paradox of plurality and the ancient proof by contradiction of the irrationality of the square root of two.

The Irrationality of the Square Root of Two

There have been countless proofs over the years demonstrating the so-called "incommensurability," or lack of a common unit of measure, for the side and diagonal of a square. It would require too much additional development to illustrate Zeno's approach using Euclid's proof for Proposition 17 of Book X in the Elements involving incommensurables. Besides, a detailed and accurate historical recapitulation is not the over-riding objective of this paper. Therefore, a more familiar variation with the additional simplification of using algebraic notation (drawing from Eves, 1945, p. 317) will suffice for my purposes here.

Note that, for a positive integer s, s² is even if and only if s is even (0).

Suppose that the square root of 2 equals a/b, where a and b are relatively prime whole numbers.

Then, a² = 2b² (1).

By (1) we see that a², and hence by (0) that a, is even. So let a=2c.

Then (1) becomes 2c² = b²,

from which we conclude that b², and hence, again by (0), that b must be even. As both a and b are even, they share a common factor, and therefore are not relatively prime whole numbers. This is a contradiction, therefore, given the truth of our lemma (0), our supposition that the square root of 2 equals a/b follows the way of seeming, and not the way of truth.

Postscript

The relations between the way of seeming and the way of truth, or the respective realms of the senses and the intellect, has been one of the most troublesome problems in the history of Western thought. It was exactly this problem that Plato was trying to put to the test with the Eleatic logic of Zeno and Parmenides, and found that his theory of forms was not dealing in a completely satisfactory manner with the problem of how these two realms were interacting with each other. Eventually, Aristotle turned Plato's metaphysics on its head. Rather than prioritizing the conceptual realm of the intellect as Plato had done, and try to solve how concepts participated in the particular sensory experiences for which they were universals, Aristotle began with the particulars, and then appealed to a process of abstraction in order to bridge this gap.

Be this as it may, there remains something deeply troublesome about the problem of the one (the universal) and the many (the particulars associated with the universal). Consider the definition of number in Book 7 of Euclid's Elements: "A number is a multitude composed of units." Notice there are two concepts that are involved here, that of a multitude and that of a unit. Now, Euclid's definition for a unit is "That by virtue of which each of the things that exist is called one." It does not seem to be coincidental that the definition of the unit implicitly seems to appeal to "things" in the plural. In fact, the definition of a unit would seem rather strange were it defined as "That by virtue of which that which exists is called one." The point I'm trying to make here is that the respective definitions of both number (as a multitude) and unit (as a one) seem to be both assuming and requiring the existence of each other.

I promised to revisit Plato's concern regarding the problem of participation in this regard. That is, how is it that the one is participating in all the particular units that constitute a multitude? If the one is truly one, then it cannot be unlike itself in any way, in any of its instantiations as a unit. But if it is unlike itself in any way, in any of its instantiations as a unit, then how can one unit be distinguished from another? That is to say, how can there be many? Yet Parmenides tells us that the one is everlasting, unchanging, and eternal. The fact of the matter seems to be, that the only way that we can conceive of a number composed of a multitude of identical units is to be able to count the same one over and over again in time. I end this story then, where it began, with Zeno's paradox of plurality, but I must leave the last word on the matter with Plato:

"These are the forms of time, which imitates eternity and revolves according to a law of number. Moreover, when we say that what has become is become and what becomes is becoming, and that what will become is about to become and that the nonexistent is nonexistent — all these are inaccurate modes of expression. But perhaps this whole subject will be more suitably discussed on some other occasion."

Sources

Allen, R. E. "The interpretation of Plato's Parmenides: Zeno's paradox and the Theory of Forms." Journal of the History of Philosophy 2, no. 2 (1964): 143-155.

Epp, S. S. "A Unified Framework for Proof and Disproof." The Mathematics Teacher 91, no. 8 (1988): 708-13.

Eves, H. "The Irrationality of the Square Root of Two." Mathematics Teacher 38 (1945): 317-8.

Guthrie, W. K. C. "Pythagoras and Pythagoreanism." In The Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Paul Edwards, 37-9. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. & The Free Press, 1967.

Harris, V. C. "On Proofs of the Irrationality of the Square Root of Two." The Mathematics Teacher 1, no. 64 (1971): 19-21.

Iamblichus. Iamblichus' "Life of Pythagoras" or Pythagoric Life. Translated by Thomas

Taylor. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International, Ltd., 1986.

Kirk, G. S., and J. E. Raven. The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966/1957.

Leron, U. "A Direct Approach to Indirect Proofs." Educational Studies in Mathematics 16 (1985): 321-325.

Peterson, Sandra. "Zeno's second argument against plurality." Journal of the History of Philosophy 16, no. 3 (1978): 261-270.

Plato, "Parmenides." In The Collected Dialogues of Plato Including the Letters, edited by Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns, pp. 920-956. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ~368 B. C. E./1961.

Plato. "Timaeus." In The Collected Dialogues of Plato Including the Letters, edited by Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns, 1151-1211. Princeton: Princeton University Press, ~368 B. C. E./1961.

Redmond, C., M. P. Federici, and D. M. Platte. "Proof by Contradiction and the Electoral College." The Mathematics Teacher 91, no. 8 (1988): 655-8.

Snell, Bruno. The Discovery of the Mind in Greek Philosophy and Literature. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1982/1953.

Szombathelyi, A., and T. Szarvas. "Ideas for Developing Students' Reasoning: A Hungarian Perspective." The Mathematics Teacher 91, no. 8 (1988): 677-81.

Thompson, D. R. "Learning and Teaching Indirect Proof." The Mathematics Teacher 89, no. 6 (1996): 474-82.

Toeplitz, Otto. The Calculus: A Genetic Approach. Translated by Luise Lange. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963.

Vlastos, Gregory. "Zeno of Elea." In The Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Paul

Edwards, 369-379. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. & The Free Press, 1967.

Warden, J. "The Mind of Zeus." Journal of the History of Ideas 32, no. 1 (1971): 3-14.

Notes on Sources

A succinct introduction to Zeno's paradoxes of plurality can be found in Gregory Vlastos's article entitled "Zeno of Elea" in The Encyclopedia of Philosophy edited by Paul Edwards (1967, New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. & The Free Press), whereas a more detailed treatment of the contemporary philosophical ramifications of Zeno's second paradox of plurality can be found in Sandra Peterson's "Zeno's second argument against plurality" in the Journal of the History of Philosophy (1978, Vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 261-270). The earliest surviving reference to Zeno's paradoxes of plurality that I have come across is in Plato's "Parmenides" which can be found in The Collected Dialogues of Plato Including the Letters, edited by Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairnes, (~368 B.C.E./1961, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 920-956). For an analysis thereof, see R. E. Allen's "The interpretation of Plato's Parmenides: Zeno's paradox and the Theory of Forms" in the Journal of the History of Philosophy (1964, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 143-55). A wide variety of pedagogical approaches to proof by contradiction have been investigated. Some of those ways, as noted above, and a number of others, can be found in the special focus issue (November, 1998; vol. 91, no. 8) of Mathematics Teacher on the concept of proof. Uri Leron's reflections regarding a more direct approach to proof by contradiction are found in "A Direct Approach to Indirect Proofs." Educational Studies in Mathematics (1985, vol. 16, pp. 321-5). D. R. Thompson emphasizes the importance of talking about indirect proofs, not just doing them, in her "Learning and Teaching Indirect Proof," also in Mathematics Teacher (1996, vol. 89, no. 6). As Otto Toplitz's classic text on The Calculus: A Genetic Approach (1963) attests, the historical and philosophical origins of proof by contradiction is a story well worth talking about. There are many books dealing with surviving fragments of ancient Greek, or pre-Socratic, philosophy. The main sources I have drawn from include C. M. Bakewell's Source Book in Ancient Philosophy (1907, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons), G. S. Kirk and J. E. Raven's The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts (1966, Cambridge at the University Press), and Johnathan Barnes's Early Greek Philosophy (1987, London: Penguin Books). A more interpretive treatment of the philosophical implications of ancient Greek thought can be found in Bruno Snell's The Discovery of the Mind in Greek Philosophy and Literature (1982, New York: Dover Publications). With regard to what I consider the quintiessential depersonification of the ancient Greek Pantheon see J. R. Warden's "The Mind of Zeus" in the Journal of the History of Ideas (1971, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 3-14).

Although there is a gap of over eight hundred years between the two, Iamblichus's Life of Pythagoras (1986, Rochester: Inner Traditions International, Ltd.) contains much of interest regarding the latter insofar as the former based his work on historical sources (as questionable as they in turn may be). A more recent account can be found in W. K. C. Guthrie's "Pythagoras and Pythagoreanism," also in The Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Finally, I came across Howard Eves's proofs of "The Irrationality of the Square Root of 2" in Mathematics Teacher (1945, vol. 38, pp. 317-8) via V. C. Harris's article entitled "On Proofs of the Irrationality of the Square Root of 2," also in Mathematics Teacher (1971, vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 19-21).

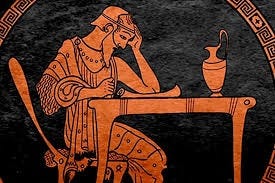

I’m pleased to refer those interested to a more recent article regarding Zeno and his paradoxes of plurality (from which the I snatched the accompanying photo). Lots of great content on that site, to which I heartily recommend subscribing:

https://socratesjourney.org/zenos-paradoxes-zeno-one-and-many/

Here is a more detailed proof by contradiction that √2 is irrational:

Assume the opposite:

Assume that √2 is rational. This means it can be written as a fraction a/b, where a and b are integers and b is not zero, and the fraction is in its simplest form (a and b have no common factors, which is jus

t to say, gcd(a, b) = 1).

Manipulate the equation:

If √2 = a/b, then squaring both sides gives 2 = a²/b².

Analyze the result:

This equation implies that a² is a multiple of 2, meaning b is also a multiple of 2 (since the square of an odd number is odd).

Contradiction:

If a is a multiple of 2, then a and b have a common factor of 2, contradicting the assumption that a/b was in simplest form.

Conclusion:

Since the assumption leads to a contradiction, √2 cannot be rational, and therefore must be irrational.

And proof by contradiction more generally:

Assume the opposite:

Begin by assuming that the statement you want to prove is false (its negation).

Derive a contradiction:

Use this assumption, along with known facts and logical reasoning, to derive a statement that contradicts the original statement or a known fact.

Conclude:

Since the assumption leads to a contradiction, it must be false. This means the original statement you wanted to prove is true.

Hopefully, by now, dear reader, you have a better idea as to how this way of thinking came about. To be, or not to be, that is the question << Shakespeare’s take!